Is it time to retire the Higg Index?

Following some very public criticism of the Higg Index, including a scathing piece in the New York Times, and then the Norwegian Consumer Authority (NCA) forcing a pause in the consumer facing portion of the tool, I’ve been contemplating whether the Higg should be permanently retired. In the ten plus years that SAC’s Higg Index has been in existence, where is the evidence demonstrating that the Higg tool has produced any positive progress on environmental or social impacts?

About the Higg MSI

The Higg Index is a sustainability assessment tool developed and launched by the Sustainable Apparel Coalition (SAC) in 2012. SAC is a pay-to-play member organization, and a brand must be either be a paid SAC member or a paid non-SAC user to access the Higg. It was adapted from two previously existing sustainability measurement standards: the Nike Apparel Environmental Design Tool and the 2007 Eco Index created by the Outdoor Industry Association and Patagonia. The tool is supposed to assess a material’s “sustainability” by measuring environmental and social impacts across various data points (water use, CO2, etc).

Over the years it has gone through various iterations, and is now

a…set of five tools that together assess the social and environmental performance of the value chain and the environmental impacts of products, including the Higg Facility Environmental Module (FEM), Higg Facility Social & Labor Module (FSLM), Higg Brand & Retail Module (BRM), Higg Materials Sustainability Index (MSI), and

Higg Product Module (PM).(from SAC website: Higg)

The Higg MSI is the most well known and referenced tool from this suite.

Why the Higg fails

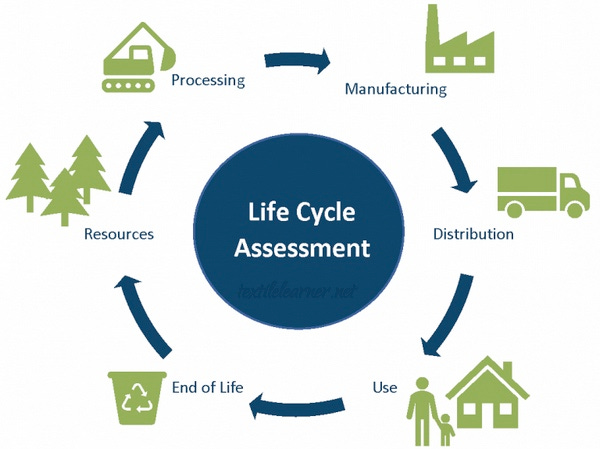

The Higg relies on something called a Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) to determine fiber impact. An LCA is a method used to measure and evaluate the environmental impact of a product from the extraction and processing of the raw materials — through the manufacturing, distribution, and use of the product — to recycling, and final disposal.

However Higg’s LCAs do not span the entire value chain. First, they only account for production through distribution to retail (cradle to gate), rather than through to consumer use and disposal/recycling (cradle to grave or cradle to cradle). Cradle to grave can provide a much more accurate assessment of apparel environmental impacts because it includes wear, laundering, and disposal impacts.

Second, Higg’s cradle to gate methodology fails to account for the catastrophic effects of synthetic textile production, including the extraction, release and transport of fossil carbon stores, and the release of microplastics into our ecosystems. By omitting these impacts, Higg’s methodology creates an inherent bias towards synthetic fibers: since the launch of the Higg tool in 2012, polyester production has increased nearly 50%.

Third, Higg MSI’s life cycle assessments use different methodologies across different fiber types, rendering the measurement framework arbitrary. Shifting boundaries for what falls into a methodology for one product and not for another produces results that are not comparable.

Fourth, the quality of the data that Higg uses to arrive at their conclusions is very poor: it’s outdated, relies on averages which lack context, and does not account for specifics or fluctuations of circumstance. For example, water use for growing cotton — conventional or organic — varies greatly by region, crop management, type of irrigation, climate, and weather. An accurate water footprint depends on where the water is taken from and when, and is critical to understanding the true impact on limited freshwater sources.

Finally, sustainability measurements must include socioeconomic impacts and outcomes. Brands are trying to define their sustainability solely through their material choices. I’ve said before, materials do not determine sustainability. Sustainability is not about the product, it’s the process. Environmental and social impacts are interrelated, must be assessed across the entire apparel value chain — from extraction of raw materials to manufacturing through to consumer use and disposal — and evaluated in totality.

The Higg MSI is the most referenced and employed tool by big brands. It’s a top down scheme, developed by industry insiders for industry insiders. While not all industry innovations are designed to be deliberately deceptive, the reality is that ALL industry innovations are designed to benefit industry monetarily. Perhaps at the outset SAC and Higg truly thought they could balance sustainability and fiscal growth. However we know that unmitigated linear growth is not compatible in any way with sustainability. Yet rather than seriously evaluate the criticisms, SAC, Higg and their defenders dug in their heels. This is not sustainable.

Why the Higg should be retired

Supporters of the Higg often say, “Don’t let perfect be the enemy of good,” a misquote of a phrase often attributed to Voltaire. What he was trying to say was that where a concept of the “best” exists, “good” will never be good enough.

Nevertheless, supporters of the Higg attack critics for wanting a “perfect tool.” They are assuming that the Higg is a “good” tool.

I am one of those critics: the Higg is not a “good” tool.

Therefore I don’t want a perfect tool: I’d like to see the Higg MSI retired. Tools like the Higg are top down solutions that serve the C-suite and shareholder board to protect profitability and propel growth.

Supporters also claim critics do not offer solutions. We do offer solutions, but our solutions are not what brands want to hear. They aren’t tools or tweaks to tools, or top down protected assets that satisfy brands’ unbridled growth agenda. What critics like myself want to see are concrete, meaningful actions that will considerably reduce the harms to both people and planet. These actions include operational adjustments that:

slow down the production cycle — such that

significantly less volume is produced — thus

drastically reducing overproduction — and thus

drastically cutting waste

Yes, there are planning tools that can help reduce overproduction and waste, but the fashion industry is producing far too much product in the first place. There have been calls for consumers to cut their consumption of new clothing purchases by 75%, but the real impact would come from cutting the production of new clothes by 75%. That may sound radical, however the reality is that brands across price points—from luxury on down—have adopted fast fashion’s seasonless churn of goods, fueling consumer overconsumption. What doesn’t make it to market or is left unsold often ends up incinerated or in landfills. These are ecological disasters affecting human and planetary health.

Brands must divest from fossil fuel products (fibers and finishes) — both virgin and recycled. Slowing down the production cycle and slashing volume would significantly aid in this, but there should also be a conscious effort to rapidly move away from these fossil fuel based products. As discussed previously, recycled poly does not reduce the volume of plastics in our environment. And then there are the textile finishes, of which PFAS pose significant health risks. And no, “bio-based” synthetics are not the solution, because nearly all still contain petroleum based polymers. Less plastic is not plastic-free.

Finally, brands must strengthen their relationships with suppliers through investment. Such investments would ensure that suppliers can then make the necessary investments in their workers and facilities towards more ethical and sustainable operations, thereby also improving the well-being of the surrounding community.

These are opportunities to bring quality back to fashion, and to produce pieces of value that (hopefully) won’t be discarded after only 1 or 2 wears. And before you say, “That’s what luxury is for,” I’d like to point out that fast fashion has been keeping clothing prices artificially low for over 20 years.

We are talking about multi-billion dollar brands here. They must shoulder more proportionate risk that for decades they have pushed on to their suppliers. Brands readily acknowledge that their supply chains are convoluted and complex. They will often point to this complexity as an excuse for not taking action: they didn’t “know” or as “buyers” they are not responsible for suppliers. But what brands fail to acknowledge is that over the last 20 to 30 years they have deliberately cultivated an increasingly complex and opaque system in which they wield their enormous financial power. COVID-19 revealed with stunning horror brands’ exploitative power over their suppliers: canceling orders en masse and refusing to pay for completed orders, thus leaving vulnerable workers unpaid and starving. More than 2 years on, workers and suppliers are still struggling.

It is true, these are primarily bottom-up solutions and investments that would require a paradigm shift in brands’ current business models. This is also what degrowth looks like:

…a planned reduction of energy and resource throughput designed to bring the economy back into balance with the living world in a way that reduces inequality and improves human well-being.

Across the globe, destructive effects of man-made climate change are everywhere: from extreme heat and fires in Europe, to unprecedented fires and floods in the US, to deadly monsoons in Pakistan. We may have already passed several tipping points, according to leading climate scientists. We are also experiencing rapidly growing income and social inequalities, exacerbated by the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic and the escalating climate crisis. These events are inextricably linked, and fashion’s extractive and exploitative practices are undeniably significant contributors. Top down schemes like the Higg Index have failed and continue to fail to address the root causes of brands’ environmental and social impacts. They are merely box-checking exercises. If the fashion industry refuses to hold itself accountable, then governments must step in and enact robust policies that compel brands to be responsible and accountable for their practices.